Deep-Dive #2: Nuclear Fusion — Changing the Geopolitical Order, One Atom at a Time

The Inexhaustible Energy Source of the Future

The joke has seemingly been around forever — nuclear fusion is 30 years away, and always will be.

Nuclear fusion technology has been defined by its many failures over the decades, but technological developments over the last 5 years and the recent surge in venture funding make it seem like this time will be different. Could nuclear fusion usher in the next renewable energy source, dramatically revolutionizing the power generation landscape? Or is the industry doomed to another round of failures?

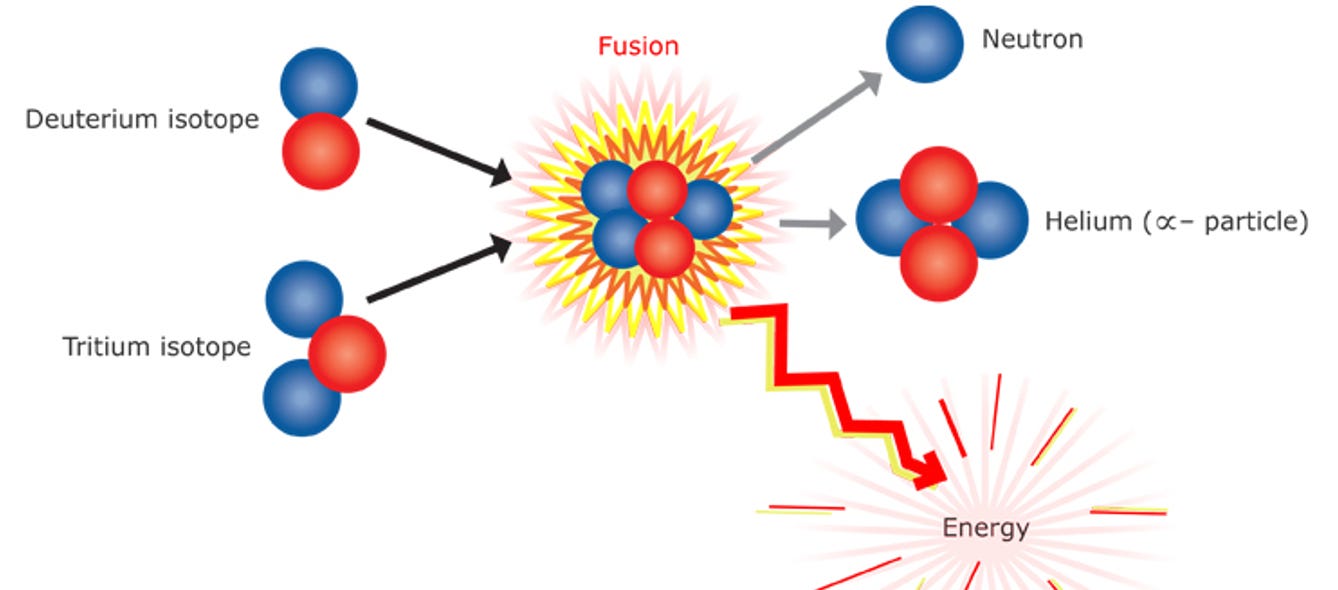

Fusion power, at its simplest, collides two lighter atoms (typically hydrogen atoms) until they fuse together into one heavier atom (in contrast with traditional nuclear power, which uses fission to split two atoms to release energy). Once the two lighter atoms combine, they have significantly more energy than the resulting heavier atom, so the excess energy is released.

Nuclear fusion can release 4,000,000 times as much energy as the burning of coal and 4 times as much energy as the nuclear fission reactions that power our current nuclear power facilities (at equal input mass) — this high potential deservedly requires extra attention.

In addition to having the highest power generation potential, its fuel source is essentially inexhaustible and the byproducts are basically carbon-free and do not result in non-radioactive waste, making nuclear fusion a seemingly utopian renewable energy source.

This deep-dive will outline the history of the industry, the different kinds of technology looking to effectively harness the power of nuclear fusion, and some (hopefully prescient) predictions for the future.

Industry History: ITER-ations of Magnets, Lasers, and Plasmas

Discovery

The first speculations around nuclear fusion came as early as 1920, when English astronomer and physicist Arthur Eddington foreshadowed the discovery of fusion processes in his research paper on stars, "The Internal Constitution of the Stars.” Nuclear fusion was scientifically proven in the 1930s, with various physicists, particularly German-American scientist Hans Bethe, uncovering more definitive and robust evidence that nuclear fusion is possible and that fusion reactions provide the energy source for the Sun.

In a 1934 experiment, renowned physicist Ernest Rutherford (most famous for his eponymous model of the atom) for the first time demonstrated the fusion of two hydrogen atoms into helium by using a particle accelerator to shoot a hydrogen isotope called deuterium into a metal foil containing other deuterium atoms. He observed that "an enormous effect” (i.e., energy release) was produced during the process.

This led to his assistant, Australian physicist Hans Oliphant, experimentally identifying the existence of certain key isotopes of helium and hydrogen in 1937 (these isotopes, helium-3 and tritium, respectively, would later become foundational for larger-scale fusion reactions).

These experiments formed the foundations that inspired the initial machines of the fusion energy race during the Cold War era.

Tokomaks vs. Stellarators

Starting in the 1940s, scientists toyed with an idea: “Can we recreate the same temperature and pressure conditions as those on the Sun to effectuate our own nuclear fusion reactions at scale?”

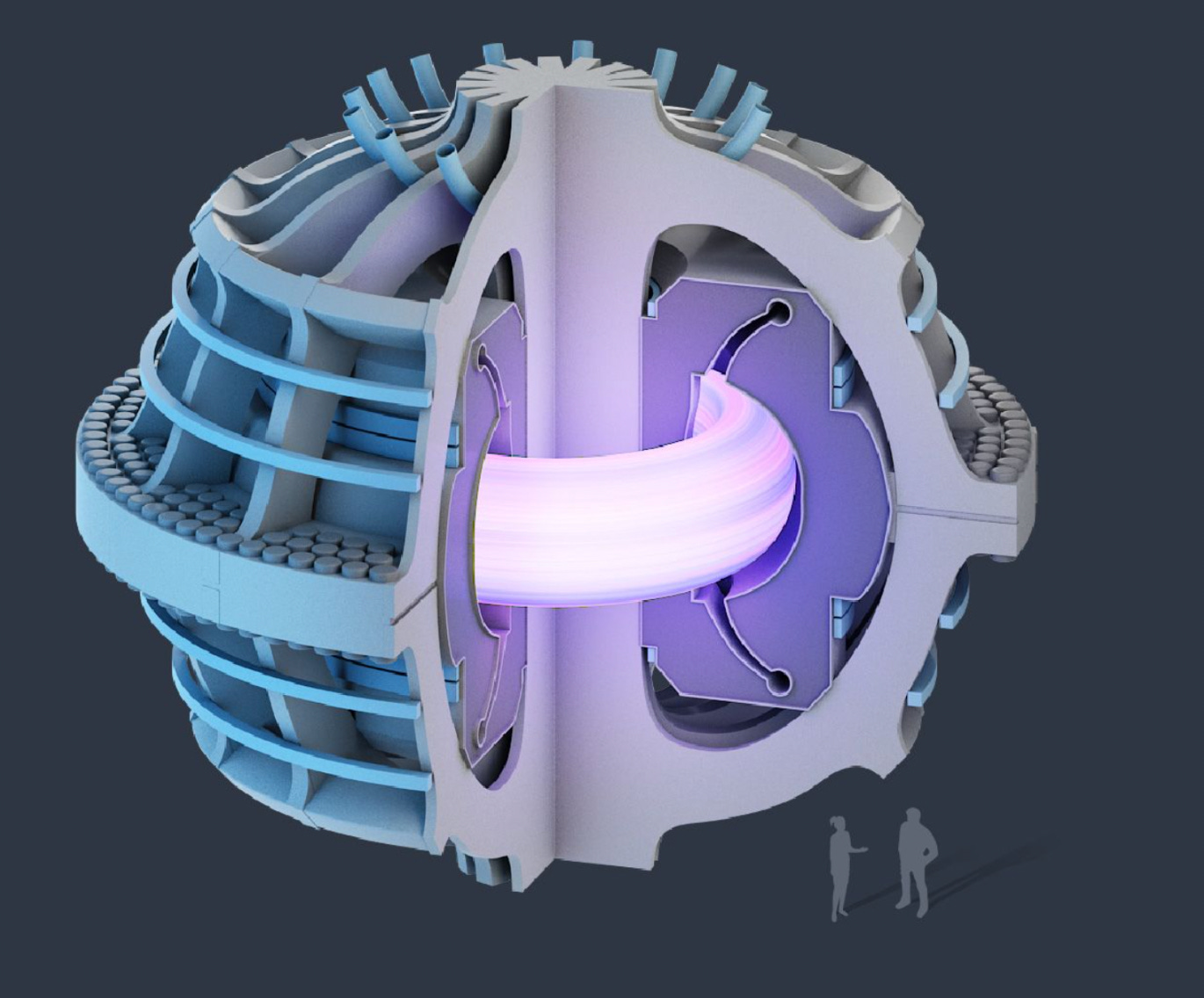

The first practical idea was proposed by Soviet scientists Andrei Sakharov and Igor Tamm in 1950. They designed a device that they dubbed a tokomak, which took the shape of a large torus (the mathematical word for a donut shape).

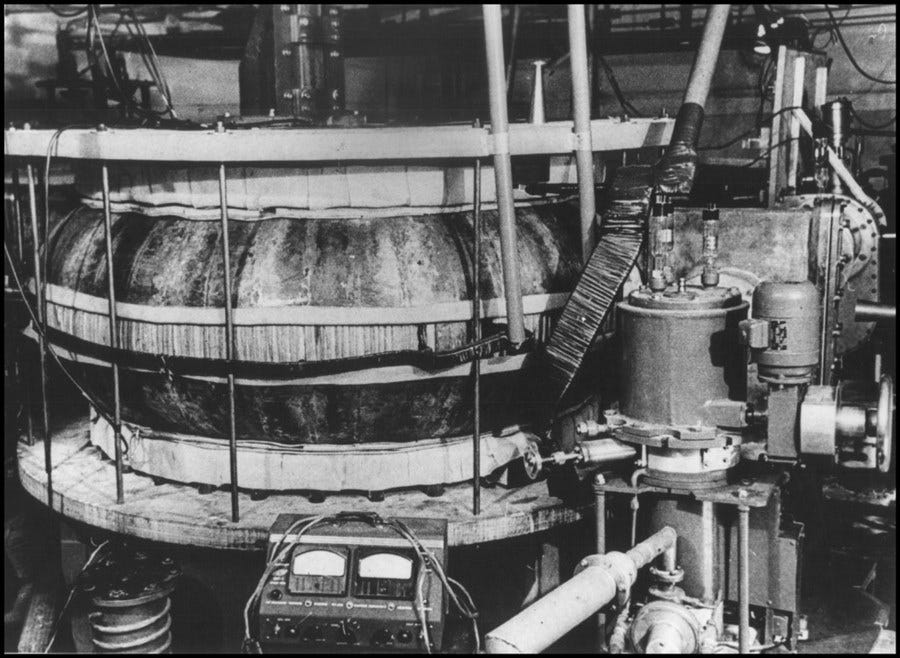

The first operational tokomak, called the T1, was completed in 1958 by a group of Soviet Union scientists, who were able to produce a hot plasma within a copper vacuum vessel.

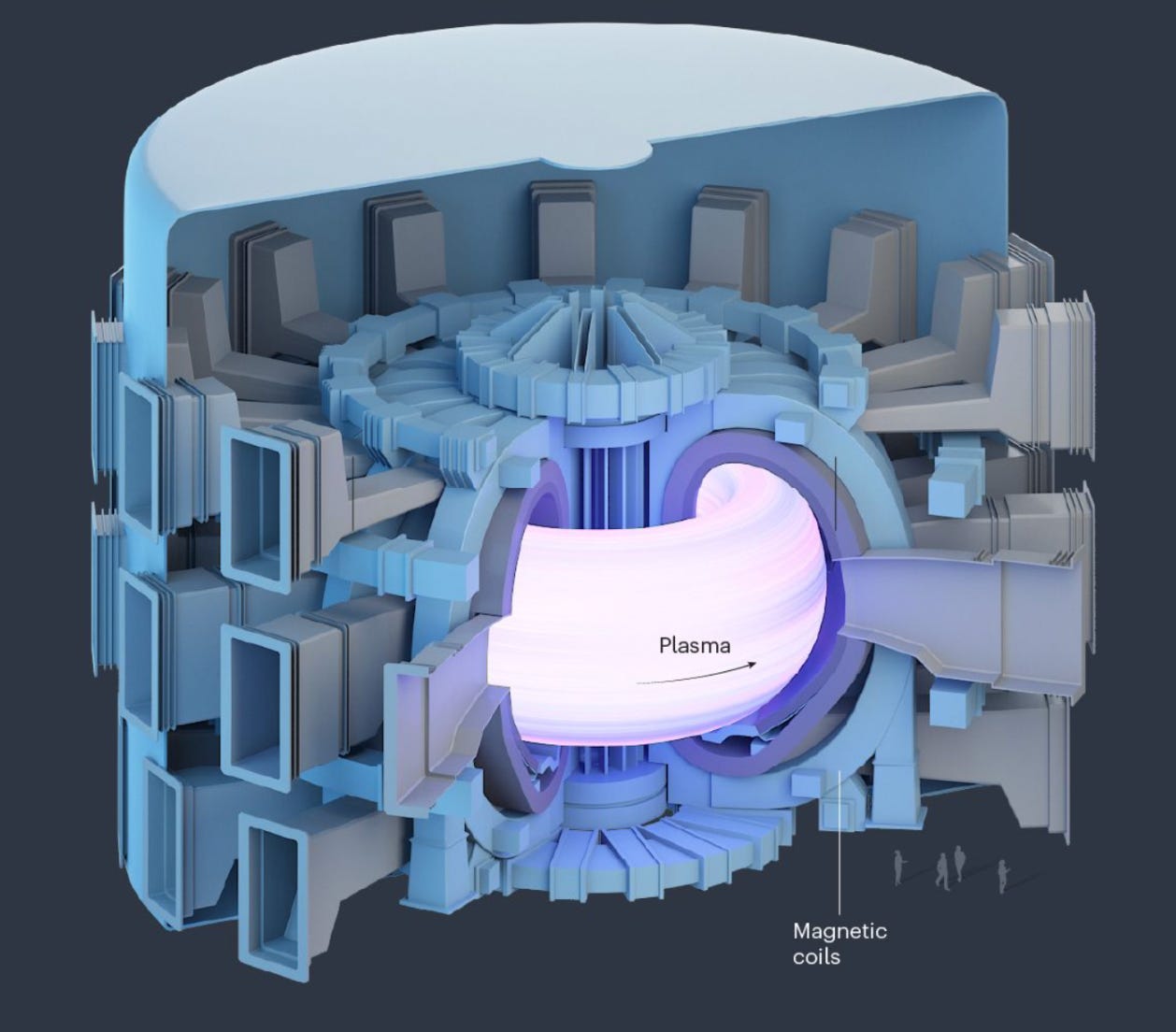

Most tokamaks, at a basic level, utilize magnetic field coils to confine plasma particles in a way that allows the plasma to achieve the high temperature and pressure conditions necessary for fusion. One set of magnetic coils generates an intense toroidal field (i.e., directed the “long way” around the torus). A central solenoid (i.e., a magnet that carries electric current) creates a second magnetic field directed along the poloidal direction (i.e., the “short way” around the torus that goes through the central hole). The two magnetic field components result in an all-encompassing magnetic field that confines the particles in the plasma.

Early tokomaks failed dramatically and could not produce any controlled releases of fusion power. The T1 tokomak demonstrated very high energy losses via radiation, which were traced to impurities in the plasma from a vacuum system catalyzing gas releases from the fusion container materials. Physicists struggled to even create the minimum 100M+ °C temperatures needed.

Then, shortly after the introduction of the tokomak, American astrophysicist Lyman Spitzer proposed the stellarator concept. Stellarators utilized magnets that twist around the plasma (vs. tokomaks where a central coil facilitated most of the magnetic field production), and many thought this would lead to much stronger magnetic fields to confine and pressurize the hydrogen plasma within. This potential caused the stellarator to briefly overtake tokomaks as the focal point of fusion research starting in the late 1950s and continuing throughout the 1960s.

In the end, stellarators flamed out even more spectacularly than the early tokomaks due to high plasma instability driven by the asymmetric nature of the magnet configuration. Stellarators were essentially declared “dead” by the fusion scientific community in the late 1960s.

Although early iterations of both tokomaks and stellarators had flaws, the international community determined that optimization of symmetrically-configured tokomaks would be the best way forward given the inherent complexities with the asymmetric, more unstable stellarators.

State of the (International) Union

After a scientific doldrums period in the 1970s, interest began to renew in the fusion space. In 1983, the Joint European Torus (JET) project in the UK was formed, and it began to take incremental steps in creating a new, more effective torus architecture.

The JET fusion device uses an improved tokomak design, which included:

A new “D-shaped” vacuum chamber that reduced forces on the plasma torus toward the center axis

A proprietary combination of advanced heating techniques that included positive ion neutral beam injection and ion cyclotron resonance heating (i.e., a supercharged microwave oven)

Massive size at ~100 times larger plasma volume contained than the next largest fusion device in production

JET broke new ground, achieving the world's first controlled release of fusion power in 1991. Then, the first experiments using tritium were carried out within JET, making it the first reactor in the world to run on the fuel of a 50-50 mix of tritium and deuterium. In 1997, using this fuel, JET set the current world record for fusion output at 16 MW from an input of 24 MW of heating.

This ratio of fusion output divided by heating input is also known as “Q.” The breakeven ratio where output is equal to input is known as “Q=1,” and to achieve net positive fusion energy, Q must be greater than 1.

JET achieved Q = 0.67, which is still the record today (although some scientists today still debate JET’s methodology for calculating Q), and JET continues to be the largest tokamak actively operating in the world today.

Another notable group is the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) Organization, which is the leading government-backed nuclear fusion research mega-project in the world. ITER actually had sewn its roots before JET — governments were looking to collaborate on fusion at a more international level, , laying out scientific research plans and engineering technical objectives over the course of the 1980s and 1990s. Nuclear fusion also became a public point of ongoing cooperation between U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev, as they attempted to foster a spirit of scientific diplomacy to help push both nations toward the end of the Cold War.

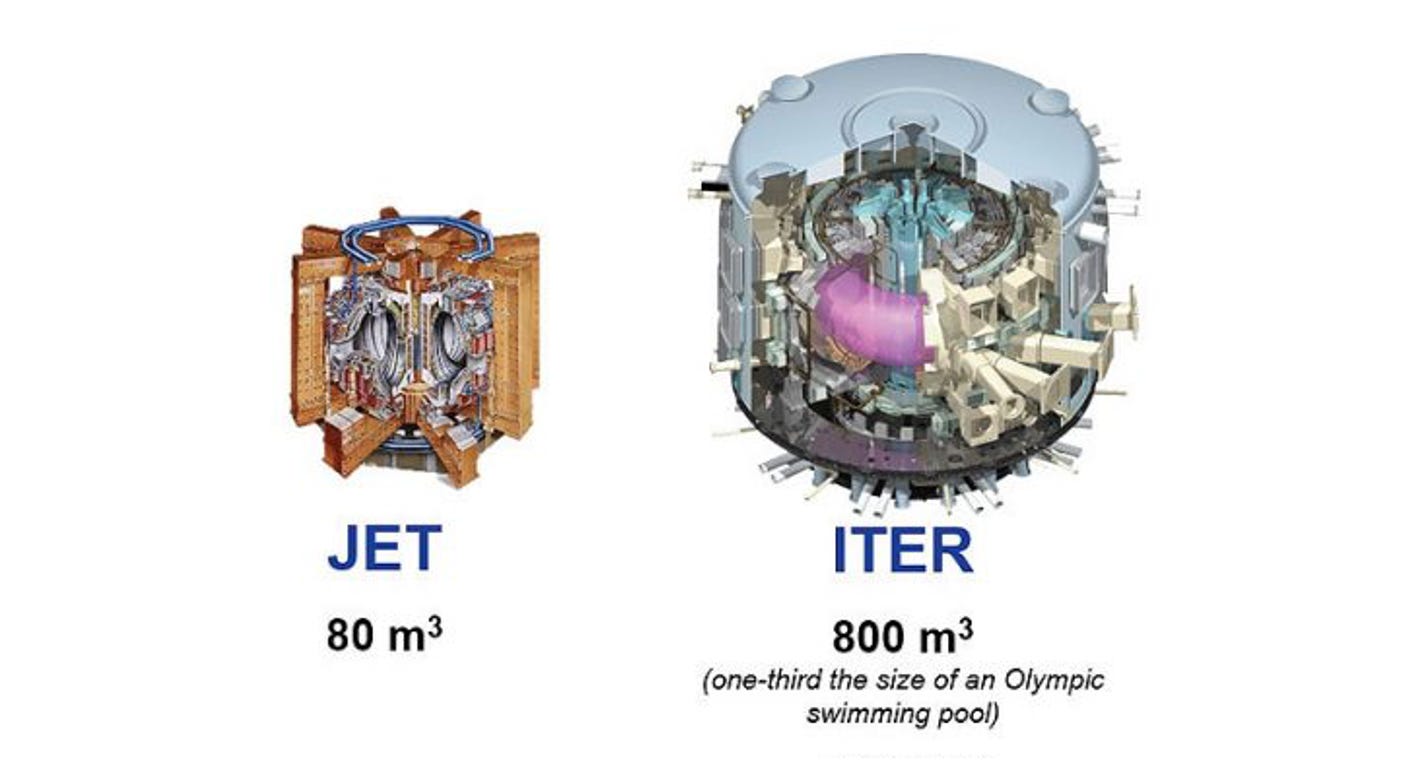

JET’s late 1990s successes inspired the go-ahead on the construction of ITER’s large-scale tokomak in southern France, which began in 2007 with initial site clearing and excavation, followed by actual tokomak construction starting in 2013, and is now expected to be completed in 2025.

ITER will be the largest nuclear fusion reactor ever built, with at least ten times the plasma volume of JET. The goal of ITER is to not just hit Q=1, but to hit Q=10 consistently for periods of 7-10 minutes.

Given its scale, the project is incredibly expensive — ITER pegs the total cost between $20B and $24B, but other estimates state that the real costs sit somewhere between $45B and $65B.

ITER has already become notorious as the most expensive science experiment of all time, the most complicated engineering project in human history, and one of the most ambitious human collaborations since the development of the International Space Station.

Private Funding Explosion

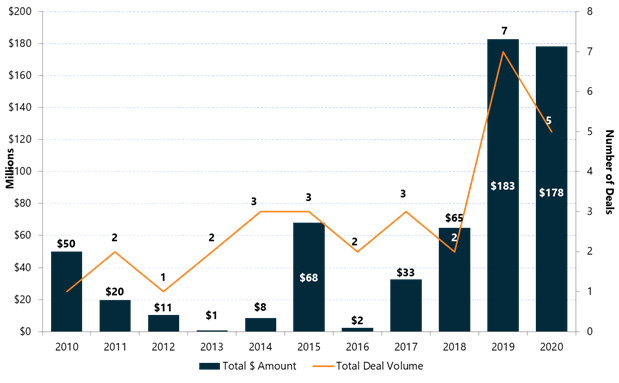

Despite all of the government-led activity in the space, privately-held companies are now playing an increasingly important role in fusion development. The Technology Breakdown below will go into detail into each of the major companies and their proprietary approaches to solving commercial nuclear fusion’s challenges.

There are over 30 privately-held nuclear fusion companies in the industry currently, and they have collectively raised over $3B in capital to date, with the vast majority of funding ($2B+) having occurred in 2021.

Funding is expected to continue accelerating into 2022 as the prospect of achieving Q=1 grows closer.

Technology Breakdown: From Physics Class to Full-Scale Fusion Reactors

Before diving into specific fusion reactor architectures, it’s important to understand the fundamental physics behind the various kinds of nuclear fusion reactions:

Fusion Basics

Successful completion of a fusion reaction on Earth typically requires temperatures of at least 100 million °C (this is approximately 6 times hotter than the Sun’s core — note that temperature requirements are higher because pressure on Earth is lower than that of the Sun). On Earth, fusion reactor technologies must use energy from microwave emitters, lasers, magnetic coils, particle accelerators, and other devices to achieve equivalent temperature conditions. At these extremely high temperatures, the superheated hydrogen gas changes state to a plasma, where all of the protons, neutrons, and electrons have come loose from their respective atoms, creating a sort of “soup” of subatomic particles.

High pressure conditions are needed to squeeze the atoms (which are both positively charged and thus strongly repel each other) extremely close to each other in order to fuse, typically as close as 1 femtometer (equal to 0.000001 nanometers) — slightly longer than the width of a proton. The Sun can create the pressure needed to overcome those electromagnetic forces due to its large mass (~330,000 times the weight of the Earth), because the resulting gravitational force compresses these masses tightly in the core. In order to achieve similarly high pressures, many nuclear fusion devices use extremely strong magnetic coils to create forces that pressurize the plasma into a state where the hydrogen atoms are forced closely together.

There are many different kinds of viable fusion reactions for commercial energy generation:

D-T Fusion

Deuterium-tritium fusion (“D-T fusion”), the most promising of the hydrogen fusion reactions, combines deuterium, which is a hydrogen isotope made up of one proton and one neutron (²H), and tritium, a hydrogen isotope made up of one proton and two neutrons (³H). The most common hydrogen isotope (e.g., the two hydrogen atoms in a water molecule) has one proton and no neutrons (¹H) — this isotope is also known as protium.

Of all hydrogen atoms found in nature, 99.99% are protium, 0.01% are deuterium, and <0.000000001% are tritium. The difference in number of neutrons is critically important for how energy is released in fusion reactions, which will become evident in the differences between the other reaction types discussed below.

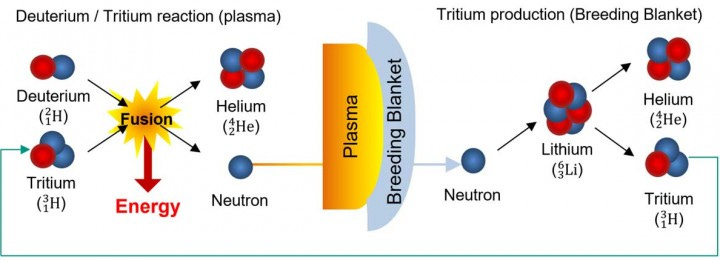

When D-T fusion occurs, the reaction results in one helium atom, one free neutron, and a large amount of energy released (shown earlier in the introduction). D-T fusion is the most common nuclear reaction used amongst all of the ongoing fusion projects in the world.

D-D Fusion

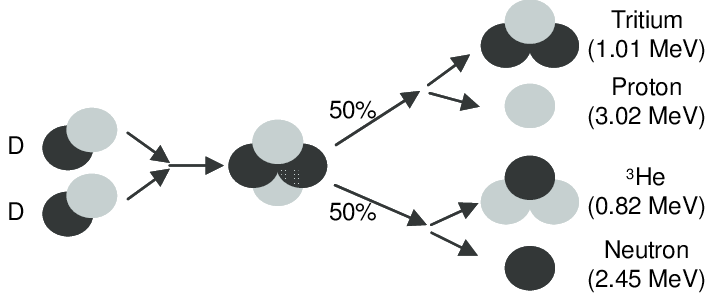

Deuterium-deuterium fusion (“D-D fusion”), as indicated by the name, involves the fusion of two deuterium atoms. Unlike D-T fusion, this is a chemical reaction that branches into two sets of products with equal probability: (1) one tritium + one protium, and (2) one helium-3 + one neutron.

D-D fusion is less promising than D-T fusion for a few reasons: (i) both particles are smaller (as compared to tritium which has more neutrons) so the probability of collision to create a fusion reaction is lower, (ii) higher temperatures (400M+ °C vs. 100M °C for D-T fusion) are required given they only have one neutron each (as compared to tritium, which has an additional neutron that decreases fusion difficulty — to be explained next).

Proton-Proton Fusion

Proton-proton fusion (“H-H fusion”) is the nuclear fusion process that fuels the Sun and many other stars. Fusing two ordinary hydrogen atoms together is extremely difficult, and their lack of neutrons is the major driver of difficulty. The deuterium isotope’s extra neutron adds mass that helps it bind more easily to another one (i.e., you don’t have to squeeze them as close together to have fusion occur).

Additionally, the net energy release from a D-T reaction is more than 40x greater than that of an H-H reaction. Therefore, this type of fusion is not practical for commercial purposes.

Deuterium-Helium Fusion

Deuterium and helium-3 fusion (“D-³He fusion”) uniquely utilizes helium-3, which is an ultra-rare isotope of helium that is used in quantum computing and critical medical imaging applications. This fusion method is different from the others in that it is aneutronic, which means that the reaction products do not include high-energy neutrons.

Note that both D-D and D-T fusion reactions release neutrons, which are ejected at high speeds and end up damaging the reactor hardware around the fusion-generating plasma — with no neutrons being released, D-³He fusion is more attractive in that regard. However, this method requires much higher temperature conditions as compared to those needed for D-T fusion (anywhere from 4-6 times as high at 400M-600M °C).

Fuel Sources

Deuterium is very abundant given 1 part in 5000 of the hydrogen in seawater is deuterium. Taking all of the seawater on Earth, this amounts to over 1015 tons of deuterium. If used efficiently in D-T reactions, a gallon of seawater could produce as much energy as 300 gallons of gasoline (~7 barrels). Taking these calculations to the extreme — all of Earth’s seawater, around 300 quintillion gallons, represents ~2 sextillion barrels of gasoline (that’s a 2 followed by 21 zeros!).

OPEC reports that there are 1.5 trillion barrels of crude oil reserves left in the world, meaning that all of Earth’s seawater represents ~1 million times more energy if used in fusion energy generation vs. the energy from burning the remaining oil left on Earth.

On the other hand, as evidenced by tritium’s de minimis abundance mentioned previously, almost zero tritium occurs in nature because it is radioactive and thus decays over time due to beta particle emission. Tritium also has a 10-year half-life (i.e., takes 10 years for ½ of the atoms within a given tritium quantity to decay), which is very short on the radioactive time scale. By contrast, Carbon-14, which is commonly used for radioactive dating fossils and other archaeological samples, has a half-life of 5,730 years. Earth’s atmosphere only has trace amounts of tritium, formed by the interaction of certain nitrogen molecules with cosmic rays (energetic subatomic particles produced by the Sun, other stars, and various other celestial bodies), and these tritium atoms only exist for a relatively short period of time.

Therefore, nuclear fusion companies utilizing D-T reactions have to invent ways to synthetically create a sustainable tritium supply. The most promising source of tritium at the moment is tritium breeding, where Li-6 (lithium isotope that makes up 7.4% of lithium found in nature) is bombarded with neutrons, causing a chemical reaction that produces tritium along with byproducts of helium atoms and energy release.

Given that neutrons are released from D-T fusion reactions, tritium breeding often involves placing a liquid “blanket” of Li-6 (which can be dual-purposed as reactor coolant) around the main reactor such that neutron byproducts strike the liquid. This reaction results in the creation of tritium atoms, which must then be transferred back into the core, where it can interact with deuterium to complete more D-T fusion reactions.

If tritium breeding is done efficiently and tritium is extracted in sufficient quantities, this creates a flywheel that allows for continued reactions via this closed fuel source ecosystem.

Ignition

Another important concept to understand in the nuclear fusion world is ignition, which is the point at which a nuclear fusion reaction becomes self-sustaining. Ignition occurs when the energy being emitted by the fusion reactions is heating the plasma fuel mass more rapidly than the various loss mechanisms that are cooling it.

A tremendous amount of input energy is required to create the initial conditions for nuclear fusion — namely high temperature and pressure — but once those conditions are met, the external energy needed to heat the fuel to fusion temperatures is no longer needed.

Ignition was achieved at small experimental scale by the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in 2021, but only at Q values that ranges from 0.10 to 0.33 (significantly below “Q=1” breakeven) — no organization or company has ever been able to reach ignition within a true commercial reactor.

Successful, sustained ignition within a commercial fusion reactor will be a key milestone for the industry, and will likely occur within a few years of reaching Q=1, if not at around the same time.

Reactor Technologies

The different kinds of nuclear fusion hardware approaches are as follows:

Traditional Tokomak

Current tokomak approaches vary greatly, but all of the privately funded companies are taking a smaller-scale “mini-tokomak” approach (at least smaller relative to JET/ITER) in order to prove Q=1, then hope to scale upward from there.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (~$2.1B raised to date; investor base includes Alphabet, Coatue, Tiger Global, Lowercarbon Capital, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, and Bill Gates) emerged from a fusion research group at MIT with a proprietary tokomak approach. Commonwealth’s key differentiator is a proprietary superconducting magnet that has broken certain magnetic field strength records, which is promising for creating the pressurized conditions to force hydrogen atoms to get close enough for fusion.

Commonwealth has attracted the most funding in the space given its renowned talent and first-mover status, but also because of intensive capital needs — the massive size of the device (relative to other private companies) and the costs of reactor maintenance due to high-energy neutronic damage have created major problems that the company is working to overcome. Commonwealth’s tokomak is targeted for completion in 2025, when the company expects to reach Q=1 sustainably.

JET and ITER, as previously discussed, are developing massive-scale tokomaks with the help of government funding. Other government-related organizations have played a role too — San Diego-based General Atomics has been a key partner for ITER, operating a leading institutional magnetic fusion research facility on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, and they have been instrumental in developing a foundational understanding of fusion plasmas.

Spheromaks

Spherical tokomaks, dubbed spheromaks, are pretty self-explanatory — they are tokomaks that take the shape of a sphere instead of a torus. The spheromak reduces the size of the central “hole” as much as possible, resulting in a plasma shape that is almost spherical, often compared to a cored apple (vs. the donut comparison to traditional tokomaks).

Proponents claim a few advantages vs. regular tokomaks: (i) higher magnetic pressures given that plasma sits closer to the center of the ring, making the effects of the induced magnetic field stronger, and (ii) greater plasma stability given the tighter design (also reduces heat loss).

Two large privately-held business taking the spheromak approach are General Fusion and Tokomak Energy.

Oxford-based Tokomak Energy ($163M; mainly backed by the U.S. and UK governments) introduced a proprietary HTS superconducting magnet that drives its fusion reactions.

Canadian firm General Fusion ($393M raised; notable investors are Jeff Bezos and M12) takes an approach that eschews massive magnets and lasers to drive fusion conditions in exchange for compressed gas pistons that can be more practically implemented.

Sheared Flow Stabilized Z-Pinch

In fusion research, a Z-pinch is a type of plasma confinement method that uses an electric current in the plasma to generate a magnetic field that compresses it. However, the pinch can cause “kinks” that effectively disrupt the plasma and interrupt fusion conditions.

Seattle-based fusion company Zap Energy ($43M+ raised to date; investors include Addition, Lowercarbon Capital, and Chevron Technology Ventures) pioneered a proprietary sheared flow stabilized (SFS) Z-pinch method, a novel fusion approach that originated from research at the University of Washington. By introducing a sheared axial flow into its fusion device, Zap Energy’s Z-pinch becomes much more stabilized, to the point where it can generate fusion reactions.

Zap Energy’s reactor core, called FuZE-Q, utilizes an electrode that pulsates in and out of a highly specialized plasma-filled enclosure that is effectuating the SFS Z-pinch. The reactor size, which may be the smallest in the industry is ~3 m³ (about the size of three large household fridges), allowing for a modular approach where eventually multiple reactors can be used in parallel to meet the end user need. The FuZE-Q reactor also does not use magnets (which make up a huge portion of tokomak costs), meaning their reactors are likely multiples less expensive than tokomaks. Zap Energy’s approach appears to be highly scalable and is worth following closely.

Field Reserved Configuration

Field reserved configuration (FRC) confine plasmas for fusion reactions in a way somewhat similar to a spheromak, but removes the toroidal field and thus allows for more simple reactor construction and design. A few companies have designed fusion reactors with the FRC principle as a foundational driver of their technologies.

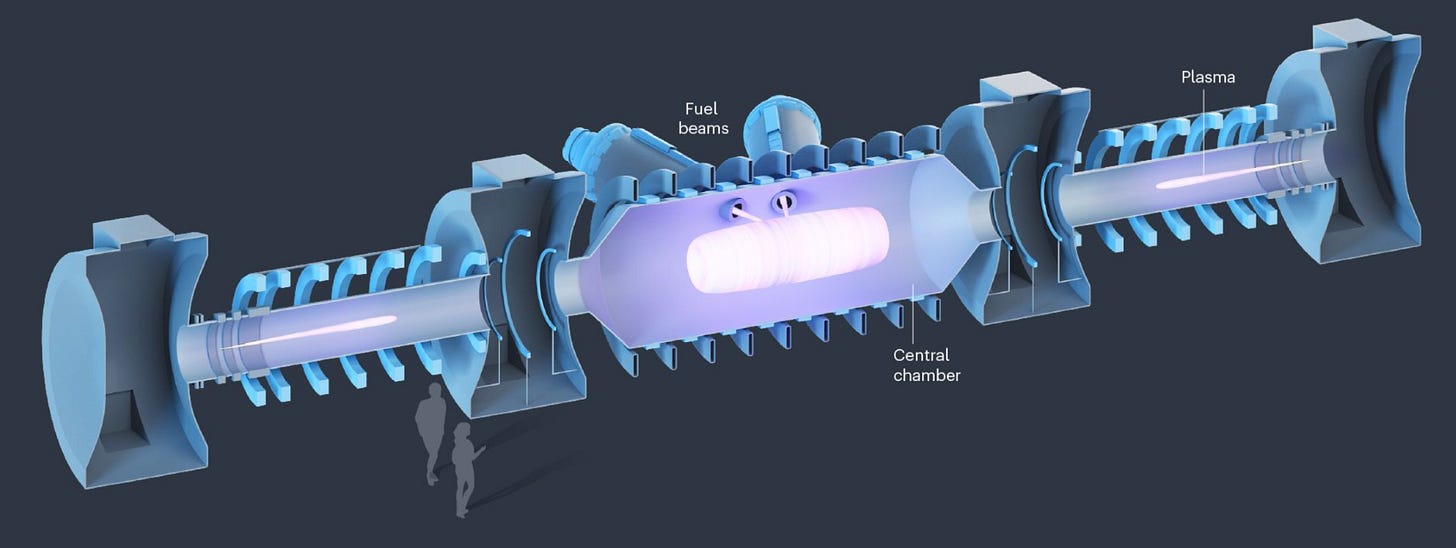

Helion Energy (~$570M raised to date; notable investors include Y Combinator founder Sam Altman, Altimeter Capital, Baillie Gifford, Blackrock, KKR, and others), located right outside Seattle in Everett, WA, is notable for its proprietary plasma accelerator that utilizes FRC. The device has an independent FRC at each end of a linear device, and each shoots a plasmoid (i.e., a blob of plasma) together at extreme velocities (over 400 km/s), compressing them to fusion conditions with strong magnetic fields.

Helion also appears to be the only well-funded player using the previously described deuterium plus helium-3 reaction, which produces helium-4 (ordinary helium), a proton, and energy. While this reaction does not produce neutrons (which is typically good because neutrons damage the reactor over time), successful fusion requires temperatures up to 600 million °C (much higher than the 100-150 million °C for more popular D-T fusion). Also, helium-3 is not abundantly found in nature, so it must be synthetically produced at scale. Helion has solved this problem by creating helium-3 through fusing deuterium in its plasma accelerator with a patented high-efficiency closed-fuel cycle.

Another FRC player is California-based TAE Technologies ($1.1B raised; investors include Paul Allen, Alphabet, NEA, and Goldman Sachs), which also utilizes an aneutronic fusion reaction, combining hydrogen with boron to output helium atoms and energy. In similar spirit to Helion’s approach, its linear reactor fires packets of plasma into a central chamber, which rotates rapidly inside a solenoid (coiled-wire electromagnet).

Inertial Confinement

While essentially all of the previous methods fall into the magnetic confinement category, a smaller subset of researchers and businesses are exploring inertial confinement fusion (ICF). This method initiates fusion reactions by compressing and heating targets filled with thermonuclear fuel, which typically take the form of pellets containing a mixture of deuterium and tritium. In most ICF applications, high-energy lasers heat the outer layer of the device, exploding outward and creating an opposite reaction force inward, creating shock waves that compress the fuel such that fusion occurs.

This field has been dominated by government research, with the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in northern California being the largest operational facility. Recent accomplishments include proof of the world’s first burning plasma, with yield estimated to be ~70% of the laser input energy.

Oxford-based First Light Fusion ($107M raised to date; Tencent was a notable recent investor) appears to be the only venture-backed business taking an ICF approach, utilizing the creation of intense shock waves to crush gas-filled cavities, inducing asymmetric collapses within a proprietary geometry that more effectively generates fusion reactions (vs. prior approaches with symmetrical collapses/geometries).

Projected Timelines

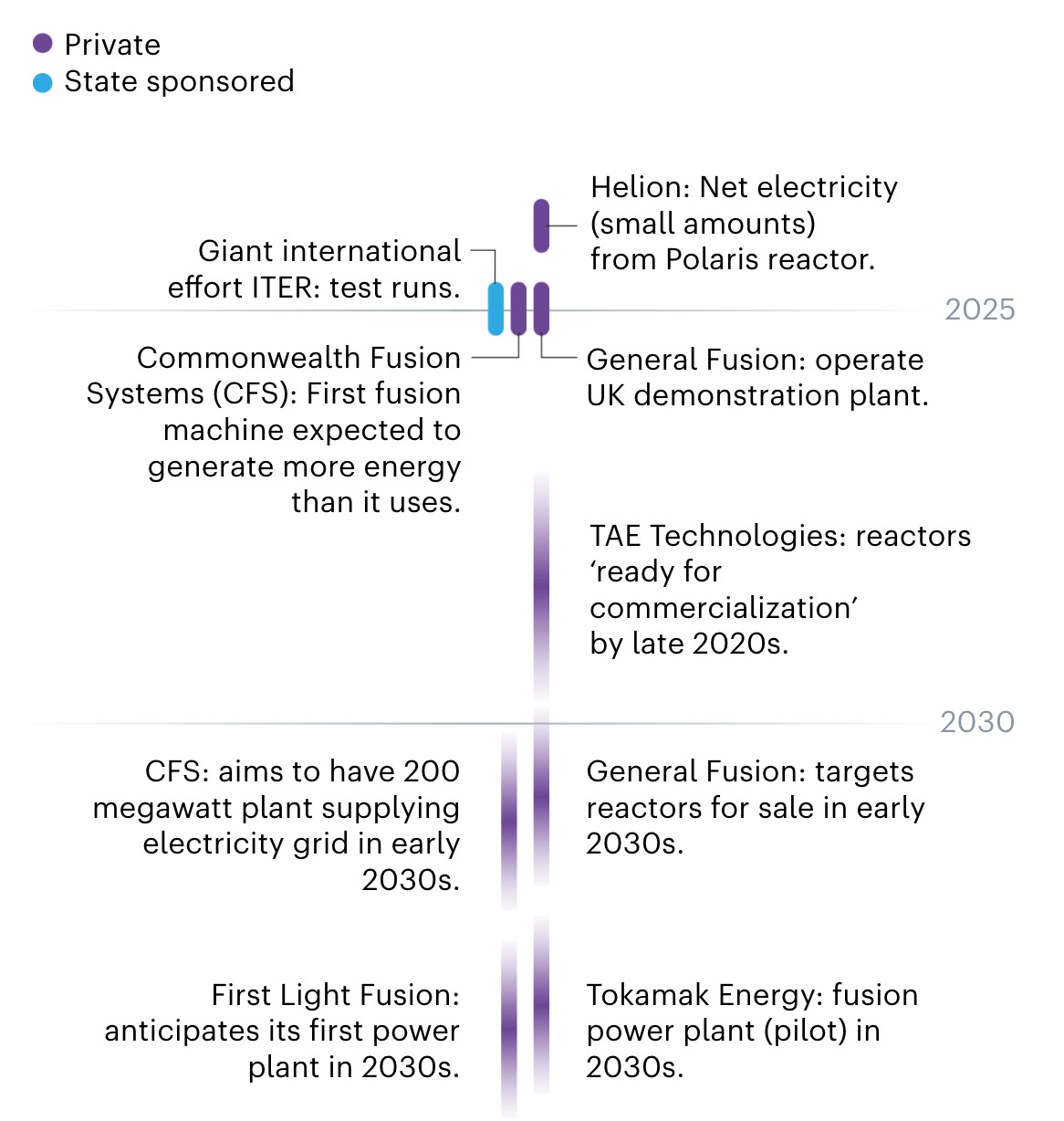

With all of these companies in mind, below is a timeline with a few selected companies and their fusion milestones for the second half of the decade.

Accomplishment of any of these milestones would be critical wins for the nuclear fusion industry. As these companies continue to see breakthroughs, it will be interesting to see which reactor technology approach gains the most traction first.

If one of these companies wins just 1% market share of the $1.2T electric power industry, it would be valued at $50B+ at bare minimum given historical EBITDA multiples and margins seen in the renewable energy sector — this is the outcome that investors in these businesses are hunting for.

Industry Predictions: Q=1, Non-Tokomak Dominance, and Funding Abound

With all of this in mind, here are my short-term (one-year) and long term (3+ year) predictions:

Medium-Term Predictions (2023-2027)

Q=1 will be achieved within the next 5 years. One of the major industry players will verifiably demonstrate Q=1 by the end of 2027. This achievement will spur another surge in venture investment, given the validation this achievement would bring to the industry — other players will also look to raise more capital for acceleration of R&D efforts to “catch up.” Given the huge fundings at the end of 2021 ($0.5B raised by Helion, $1.8B raised by Commonwealth), 2022 and 2023 will likely see several other $500M+ fundings for the other major fusion companies to further fuel the race for Q=1.

Non-tokomak companies will lead a majority of the key scientific breakthroughs over the near-term. Given that tokomaks are built with scaled power generation in mind, some of the non-tokomak players (e.g., Zap Energy, Helion Energy, First Light Fusion) will likely be able to produce groundbreaking results at smaller scale using their unique, more cost-effective approaches.

One of the major companies in the space will go public in 12-24 months, drawing further positive attention (and more intense scrutiny) to the industry. Pre-revenue companies in certain deep-tech sectors have been going public very early, with the best example industries being quantum computing (now-public companies include IonQ and Rigetti Computing) and solid-state battery technology (QuantumScape and Solid Power) — all of which do not expect to generate significant revenue until 2025 at very earliest. Many of these companies also face short-seller reports doubting scientific efficacy and development timelines. The nuclear fusion industry has similar dynamics (except the commercialization timeline is even longer). Odds are that one of the largest players will go public in order to give early shareholders liquidity and to tap into a broader swath of funding from the public markets given the capital intensity of their R&D.

Long-Term Predictions (2028 and Beyond)

Tokomaks will make a lot of positive headlines and continue to raise astronomical amounts of money, but they won’t be the best long-term solution. Even when tokomaks eventually hit Q=1, they will inevitably have to come to terms with what could be insurmountable setbacks, including exorbitant upfront costs (will likely always be in the billions of dollars) as well as high costs of maintenance due to seemingly unavoidable neutronic damage (plus indirect costs of repair downtime). While they might be able to power a few electrical grids, long construction times and high costs will hamper scalability and cause them to fall behind other industry players in terms of growth.

Privately-funded companies will trump government-sponsored projects. While JET, ITER, and others like them are making important advancements for the fusion space, long-term commercialization will be best accomplished by private companies. The best talent is being accumulated at the current venture-backed companies, who are paying top-tier salaries and offering significant equity upside to employees. Human capital is the biggest challenge in this highly specialized industry, and the companies who can recruit and retain the most high-quality people will innovate most and eventually win. Private companies will end up driving 80%+ of eventual electrical grid generation from fusion.

Nuclear fusion will enter the electric grid sometime between 2032 and 2035, then fusion will make up at least 1% of total U.S. electricity generation by 2045. While not a perfect analogy by any means, traditional nuclear energy (which now powers nearly 20% of the U.S. electrical grid), increased from essentially zero in 1960 to nearly 2% of total U.S. electricity generation in 1970 – fusion could follow a similar trajectory over the 10 years following wider-scale grid integration.

Tying it All Together

Taking a step back and examining the problem at an astronomical scale, the Sun (which accounts for 99.86% of the solar system’s total mass) is a giant ball of hydrogen sustained by fusion reactions that have been ongoing for billions of years within its core. Fusion reactions underpin the galaxy and our existence, and now humans have the tools to harness this phenomenon for ourselves.

Even our elected officials are starting to understand the enormous potential of the nuclear fusion energy solution.

Senator Joe Manchin, who is a pivotal figure in U.S. energy policy as the Chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, very recently visited the ITER project site on March 25th. He eloquently stated another future impact of fusion energy:

“Today I saw the possibility of world peace. Because I don't think, in the annals of history, we've ever had a war that was not in some way about energy. What you are all doing here is laying the ground for world peace."

Fusion energy is not just about creating a new efficient energy source. The successful fusion companies will upend the energy sector, change geopolitical status quos, and create trillions of dollars in value.

The biggest question is when.

— Dillon

Note: Key source used for many of the images was Nature, from article titled “The chase for fusion energy”

![First Light Fusion’s Big Gun to be launched by UK Science minister Amanda Solloway today[2] First Light Fusion’s Big Gun to be launched by UK Science minister Amanda Solloway today[2]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!LETM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7a1aea60-2eb7-4425-b332-6ffb9cdaccf3_787x626.jpeg)